Who Benefits From a Delayed Future?

Defenders have the status quo have little to lose from ignoring or undermining AI adoption.

Teddy Roosevelt is twisting in his grave. The Rough Rider, the Trust Buster, the Trail Blazer—Roosevelt feared failure far more than he feared the unknown. Americans followed his lead. They trusted him to oversee new policies, programs, and initiatives that disrupted the status quo.

Yet, Americans today seem to have forgotten one of his most enduring quotes:

It is far better to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.

Too many of us have become followers of prophets of doom—politicians, "thought leaders," podcasters, and influencers encouraging us to not only consider but to expect that only darker days lie ahead. They tell tales of gloomy hypotheticals that distract from the very real possibilities of progress in the here and now. They warn of institutional collapse without pointing out the institutions that are functioning and ripe for engagement. (If you’re in need of an example, check out Washington County, Wisconsin, where a novel affordable housing scheme at once increases the housing stock while also encouraging community service).

What's worse is that many of these forecasters sit in positions of power and emerged from elite backgrounds. In short, they should know better because they have received opportunities denied to others and benefited from the very institutions and technologies that they claim the rest of us should fear.

This mentality is particularly concerning when it comes to teaching law students about AI. At a recent conference on law and AI, several professors incited panic among attendees, which included several students. One warned, "AI is making everything worse." Another cautioned, "AI is coming for you." These hyperbolic and largely unfounded descriptions may grab attention but risk undermining the success of the students relying on their professors for guidance and knowledge. Unlike those professors, students today do not have the luxury of ignoring AI nor delaying their adoption of this pervasive technology.

The reality is that AI is already transforming legal practice in ways that extend far beyond the apocalyptic scenarios often presented. Document review software powered by machine learning has for years been reducing the time attorneys spend on tedious tasks. Contract analysis tools can now identify potential risks in agreements within minutes rather than hours. Legal research platforms use natural language processing to surface relevant precedents that might otherwise remain buried in obscure case law. These advancements don't eliminate legal jobs—they elevate them, allowing attorneys to focus on the uniquely human aspects of lawyering: strategic thinking, client counseling, and courtroom advocacy.

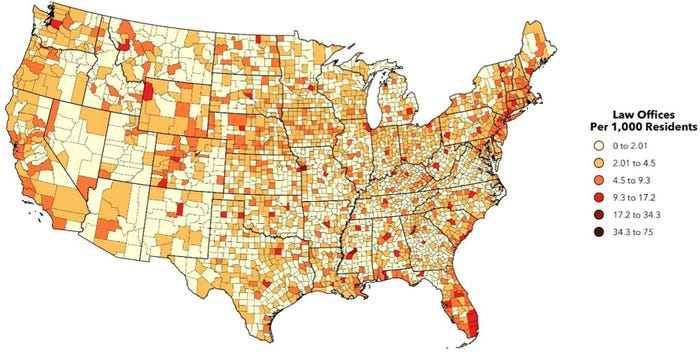

Students who grasp AI will not only experience more success in the workforce but can also help the legal profession live up to its obligation to serve the public. Imagine, for example, how AI tools available right now might improve access to justice for rural Americans by allowing them to more clearly and accurately express their rights. In states like South Dakota, where a single county might have fewer than ten practicing attorneys, AI-powered document assembly could help residents draft simple wills, power of attorney documents, or landlord-tenant agreements that otherwise would go unwritten.

Imagine if lawmakers used AI tools available right now to more thoroughly analyze the likely effects of their legislation on small businesses. AI systems could simulate economic impacts across diverse business sectors and geographies, potentially preventing unintended consequences that disproportionately harm vulnerable communities. Rather than push students to think about these positive use cases and push them to work toward them, many professors--who, again, face far fewer career consequences from being AI skeptical and illiterate--are spreading messages of doom.

A few schools have already recognized this disconnect, undergoing the difficult but necessary task of changing their curricula and course offerings. Case Western School of Law now requires first year students to earn a certificate in AI. Yet many law schools lag behind, with faculty members sometimes proudly announcing their technological ignorance as if it were a badge of honor rather than a professional liability.

Yes, some AI tools present significant risks. The leading models deployed by OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google may ease the creation of biological weapons, for example. Advanced language models can generate convincing disinformation or deceptive legal arguments that might mislead courts. These concerns deserve serious attention and robust regulatory frameworks. Beneficiaries of the status quo want us all to focus exclusively on those advanced tools and their potential harms. They're right that a small fraction of lawyers, regulators, and civil society generally should worry about those potential use cases. However, the vast majority should realize that AI is here to stay and that a failure to equip students for that future amounts to professional malfeasance.

In conclusion, Roosevelt's call for daring greatly has been drowned out by a chorus of unproductive panic by individuals who profit from paralysis rather than progress. This risk-averse mentality particularly damages our approach to AI, where elite voices with secure positions ironically discourage the very innovation that could democratize opportunity. While vigilance about potential dangers remains essential, we fail to live up to Roosevelt's legacy when we allow hypothetical threats to overshadow tangible benefits. The true risk isn't in AI's advancement but in our collective retreat from its possibilities. By reclaiming Roosevelt's courage to venture boldly into the unknown, we can harness these tools to strengthen our institutions and expand access to justice rather than cowering in the "gray twilight" of technological hesitation. The future belongs not to those who fear change, but to those brave enough to shape it.

Kevin, I appreciate your case for techno-optimism generally. But I have more confidence in AI as a means to the end of discovering new medical cures and engineering new methods to reduce or capture carbon in the atmosphere than I do for delivering products that can be trusted for consumers. When it comes to written documents, I'm skeptical -- not of the benefits of bypassing intellectual grunt work but of the credibility of documents it produces. If I'm having a will drafted by AI, how do I know it's reliable and legally sufficient and who will be responsible for flaws if it's not. The advantage to me for having an attorney (a human attorney certified by the bar) "look it over" is worth more than the convenience of downloading a document from the cloud. I hope you and others of your generation can give us oldsters some guidance about how we can trust and verify the intellectual products that will proliferate in this new AI marketplace.