The Faulty Assumption Behind the AI & Copyright Debate

Copyright law protects gatekeepers, not creators. AI policy built on this broken foundation will entrench inequality while missing what artists actually need.

Protection of existing copyright law is not the same as protecting individual creators.

Protection of existing copyright law does not drive a diverse range of artists to paint, songwriters to pen lyrics, and authors to draft manuscripts.

Protection of existing copyright law will not sustain the creative economy.

I’d go on, but I think you get the point.

Advances in AI mean that we need to have a deep conversation about how to cultivate and sustain a market for creators. That’s a distinct conversation from whether we should inhibit AI training on copyrighted material. Until this fact is made clear, we will continue to debate the wrong question in AI copyright discussions.

To understand why these are separate questions, we need to examine who copyright law actually serves in practice. The answer reveals a system quite different from the one we imagine when we invoke the solo artist or independent creator in debates over AI. That disconnect between perception and reality starts with a fundamental feature of copyright enforcement itself. It’s not easy to enforce a copyright claim in light of infringement, as explored in more detail below.

While it’s true that copyright protection occurs with the creation of the work itself, mere creation does not grant the copyright holder the ability to bring an infringement action. A creator must have registered their copyright if they want to enforce that intellectual property in court.

This fact raises two questions:

Who actually registers copyrightable materials?

How difficult is it to bring and win an infringement action?

Answers to these questions will reveal the extent to which it’s important to read existing copyright law as foreclosing the use of copyrighted materials as part of AI training data. If a wide range of smaller creators both register and defend their copyrighted materials that will serve as evidence of the need to make sure that AI labs do not deprive creators of this essential vehicle for protecting their creative endeavors.

If the opposite is true—that the small-time creators allegedly at the heart of this debate do not register or enforce their copyrights, then there’s a strong case to be made that how best to compensate and support those individuals in the Age of AI should turn on factors other than a bespoke reading of copyright law and, by extension, the Intellectual Property (IP) Clause of the Constitution that authorizes Congress to pass such laws in the first place.

WHO ACTUALLY REGISTERS THEIR COPYRIGHTED MATERIALS?

Not who you think.

Copyright is a tool predominantly relied on by individuals and organizations in just five cities:

New York

LA

Philly

DC

Chicago

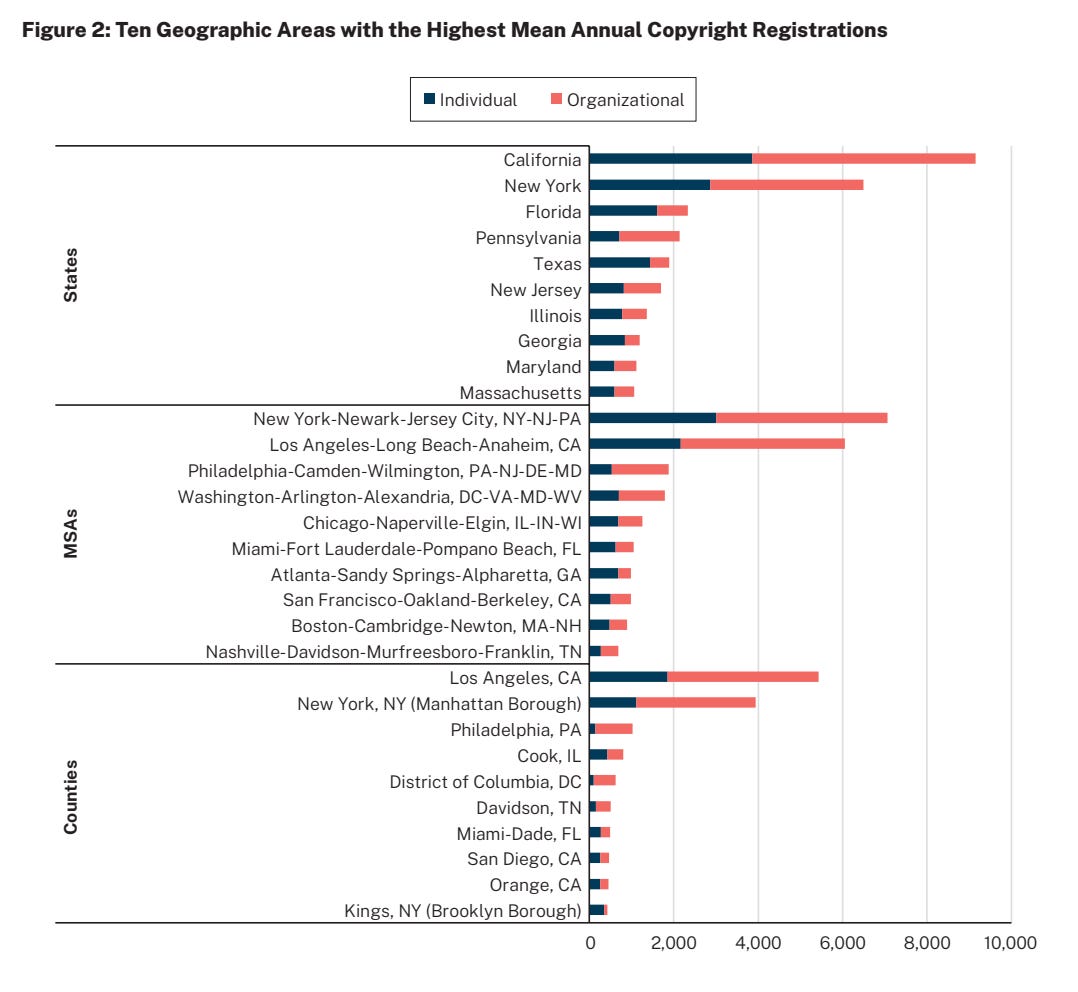

Forty percent of all copyright registrations are from these cities. More generally, according to the U.S. Copyright Office, “the majority of copyright registrations originate from a handful of large metropolitan areas.” This geographic disparity is even larger for certain types of works. Nearly 75 percent of art work registrations are from the ten largest states. As Figure 2 makes clear, the maintenance of the existing system is of most importance to a select few places.

This geographic limitation is of constitutional significance. The IP Clause is first and foremost intended to facilitate the spread knowledge across the country. Put differently, the aim of intellectual property laws is the resulting public benefit from tinkerers and innovators pushing the bounds of various fields and creating products that increase the general welfare. If only a handful of communities are actually leaning on the IP system as a means to create and protect their works, then this utilitarian, nationwide purpose starts to come into question. If California and New York dominate the tallies of copyright registrations, there’s reason to believe that they are garnering a larger share of the resulting private and public benefits from that protection. This conclusion suggests that existing law is failing to incentivize creative work around the country. That seems to clearly run afoul of the purpose of the IP Clause.

It’s not just that copyright registrations are confined to a few locations, it’s also disproportionately the tool of a small, unrepresentative segment of the population within those communities.

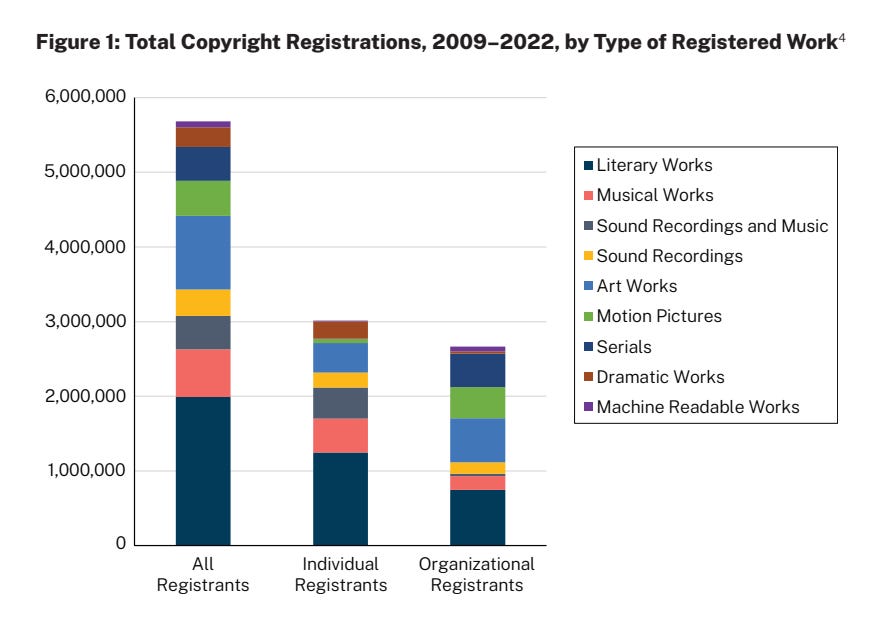

Organizational claimants make up a large percentage of registrations. These claimants are not the small, entreprenuerial creators often mentioned in AI copyright debates. A few realities about this group merit attention:

They are often not even the author of the work. Organizations may have acquired a copyright from the original creator, which means that enforcement of such copyrights may have little to no benefit to the small artist or band.

They are generally “record labels, movie studios, or literary publishers” as well as “trade associations, and universities.”

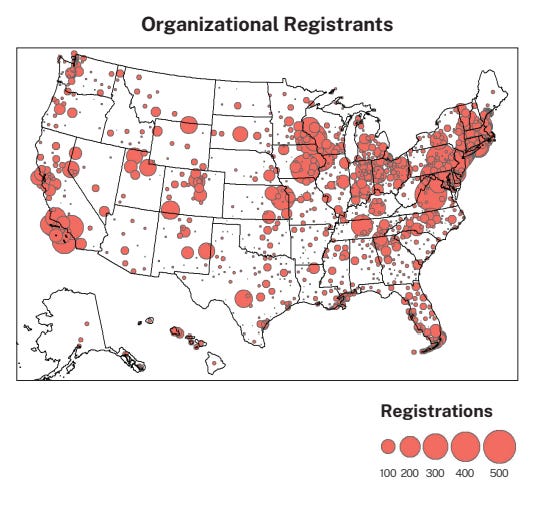

They are confined to a very small number of communities around the nation, as shown below.

I have no beef with the very real need to help protect and sustain the ability of these organizations to share incredible and important works. There’s real economic and social value in ensuring that companies like Apple, Netflix, and the like can make the shows we all binge, for example. But I take immense issue with the notion that defense of the status quo is a fight for the little creator.

The wide gulf between the actual demographics of copyright registrations and the narrative that this is a fight for the garage band down the street is further amplified by looking at the typical profile of individual copyright registrants. Here are a facts about these individuals worth flagging:

Women make up just 38.5 percent of authors of registered works as of 2020.

White authors account for a substantial share of copyright registrations relative to their slice of the population.

in 2010, the Census Bureau calculated that whites were about 63.7 percent of the population.

yet, per Robert Brauneis and Dotan Oliar, “as of 2010, white authors were producing 116 percent of the registrations they would be if they were producing at a rate equal to their proportion of the general population[.]”

meanwhile, the average age of a registrant is around 40 for both male and female authors.

In short, it does not appear that copyright laws are evenly and adequately driving creative work among the American population. This contradicts the utilitarian motives underpinning the IP Clause. Brauneis and Oliar convincingly make this point:

We cannot . . . see how a utilitarian could seriously argue that policymakers wishing to advance efficient social production of creative works should not care—and indeed do not need to know (let alone know why)—that women, half of the population, currently comprise only 36 percent of registered authors[.]

The Supreme Court has frequently announced that laws grounded in the IP Clause must be based on their actual effect on the creation and spread of knowledge. Chief Justice Marshall, for instance, clarified that the “great object and intention of the act is to secure to the public the advantages to be derived from the discoveries of individual.” Realization of that goal would result in a great number of people producing a great number of works based on the possibility of securing and enforcing their copyrighted works in the event of infringement.

WHO ACTUALLY ENFORCES THEIR COPYRIGHTED MATERIALS IN INFRINGEMENT SUITS?

Again, not who you’d likely think based on debates about AI and creators taking place in the press.

Only individuals and organizations that registered their copyright may bring an enforcement action in court. So, as established above, this is already an unrepresentative group of potential enforcers.

The costs of enforcement (i.e. identifying the infringer, hiring a lawyer, spending time in court, etc.) combined with the uncertainty of how the court will ultimately adjudicate your claim mean that even fewer registrants are likely to bring suits to court. “As a practical matter, except for large corporate copyright owners, our current copyright laws are virtually unenforceable when it comes to the infringement of visual works,” based on research by the Graphic Artists Guild. The American Photographic Artists go even further, alleging that “the current system deters authors from asserting their rights, renders these cases difficult for any attorney to take on, and encourages copyright infringement by all phases of society.” Even the American Bar Association has realized this system does not align with the needs of small copyright claim holders. The ABA called for a distinct system for adjudicating small copyright claims.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR THE AI DEBATE

The data presented above forces us to confront an uncomfortable reality: the copyright system we’re being asked to protect in the name of creators is not, in fact, a system that most creators can meaningfully access or enforce. This matters profoundly for how we approach AI policy.

When we frame the AI training debate as fundamentally about copyright infringement, we’re building policy on a foundation that already excludes the vast majority of creative workers. We’re protecting a mechanism that serves organizational claimants in five metropolitan areas while claiming to defend the photographer in Omaha, the songwriter in Birmingham, or the illustrator in Portland. This is not merely rhetorical sleight of hand—it’s a category error that will lead us to construct the wrong solutions.

Consider what’s actually at stake. If we restrict AI training on copyrighted materials, we’re not primarily protecting individual creators who lack the resources to register and enforce their copyrights anyway. Instead, we’re protecting the gatekeepers—the record labels, studios, and publishers who already dominate copyright registrations and have the legal infrastructure to defend them. We’re entrenching the very concentration of creative-industry power that limits opportunities for emerging artists.

This isn’t to say that concerns about AI’s impact on creative workers are misplaced. They’re urgent and real. But the mechanism matters. Copyright law, with its demonstrated geographic, demographic, and institutional biases, is the wrong tool for that job.

The Supreme Court’s utilitarian standard for intellectual property law—that it must actually promote the progress of science and useful arts across the population—gives us a framework for thinking clearly here. If existing copyright law fails to incentivize creative production among women, people of color, and creators outside major coastal cities, then doubling down on that system in response to AI doesn’t serve the constitutional purpose. It simply calcifies existing inequalities while constraining technological development.

What would a creator-focused approach look like instead?

It would start by acknowledging that most creative workers already operate outside the copyright enforcement system. It would recognize that the garage band, the freelance designer, and the independent author need sustainable income streams, not theoretical legal protections they can’t afford to invoke. It would ask: how do we ensure that human creativity retains economic value when AI can generate similar outputs at scale?

These questions point toward solutions quite different from copyright restriction. We might consider:

Portable benefits systems that provide baseline economic security for creative workers, untethered from their ability to register and defend intellectual property claims. Just as we’ve recognized that healthcare and retirement security shouldn’t depend on traditional employment, creative work in the AI age may require new forms of social insurance.

Regional creative development funds that address the geographic concentration revealed in the Copyright Office data. If forty percent of registrations come from five cities, we need mechanisms that actively cultivate creative ecosystems in the rest of the country—grants, residencies, and infrastructure that don’t assume access to New York or LA networks.

Reduced barriers to copyright participation for those who do want to use the system. If registration and enforcement costs price out individual creators, we might create streamlined processes, subsidized legal support, or collective licensing arrangements that make copyright practically accessible rather than theoretically available.

Direct compensation models that acknowledge AI companies are building valuable products partly through training on human-created works. Rather than preventing that training, we might require revenue sharing, establish creative worker funds, or implement other mechanisms that ensure creators benefit from AI’s commercial success—even if they never registered a copyright.

The common thread in these alternatives is that they focus on sustaining creators rather than protecting existing legal frameworks. They recognize that the question “should AI train on copyrighted material?” is downstream from the more fundamental question: “how do we ensure creators can make a living?”

This reframing also illuminates why the current debate feels so intractable. We’ve conflated the interests of large rights-holders who can enforce copyrights with the interests of individual creators who cannot. We’ve treated copyright restriction as synonymous with creator protection when the data shows these are distinct—often opposing—concerns. And we’ve failed to ask whether a legal regime designed for the printing press era, and now dominated by corporate claimants in a handful of cities, is the right foundation for addressing AI’s transformative impact on creative work.

The utilitarian purpose of IP law demands that we assess systems by their actual effects, not their theoretical promises. The evidence is clear: current copyright law concentrates benefits, excludes most creators from meaningful participation, and fails to incentivize creative production across American society. Building AI policy on that foundation doesn’t protect creators—it protects the gatekeepers while constraining the technological development that might, if properly structured, democratize creative production and consumption in unprecedented ways.

This doesn’t mean AI poses no threat to creative workers. It means the threat is about labor markets, economic power, and the value we assign to human creativity—not primarily about intellectual property infringement. Until we make that distinction clear, we’ll continue optimizing for the wrong variable, constructing policies that serve concentrated interests while claiming to defend the distributed creative class that existing copyright law already fails to protect.

The challenge before us is to design systems that actually cultivate and sustain creators in the AI age. That’s a question about economic opportunity, about removing structural barriers to creative work, and about ensuring that technological progress serves broad social benefit rather than concentrating gains among those already positioned to capture them. It’s the same essential challenge the Founders recognized when they included the IP Clause in the Constitution—but meeting it today requires us to look beyond the legal frameworks that have calcified around that clause and ask what would genuinely promote the progress of science and useful arts among all Americans, not just those in five cities with the resources to register and defend their copyrights.

Sven Lohse, a student at the University of Texas School of Law, provided excellent editorial assistance with this essay. Sven’s assistance was made possible via support from the Institute for Humane Studies (grant no. IHS019239).