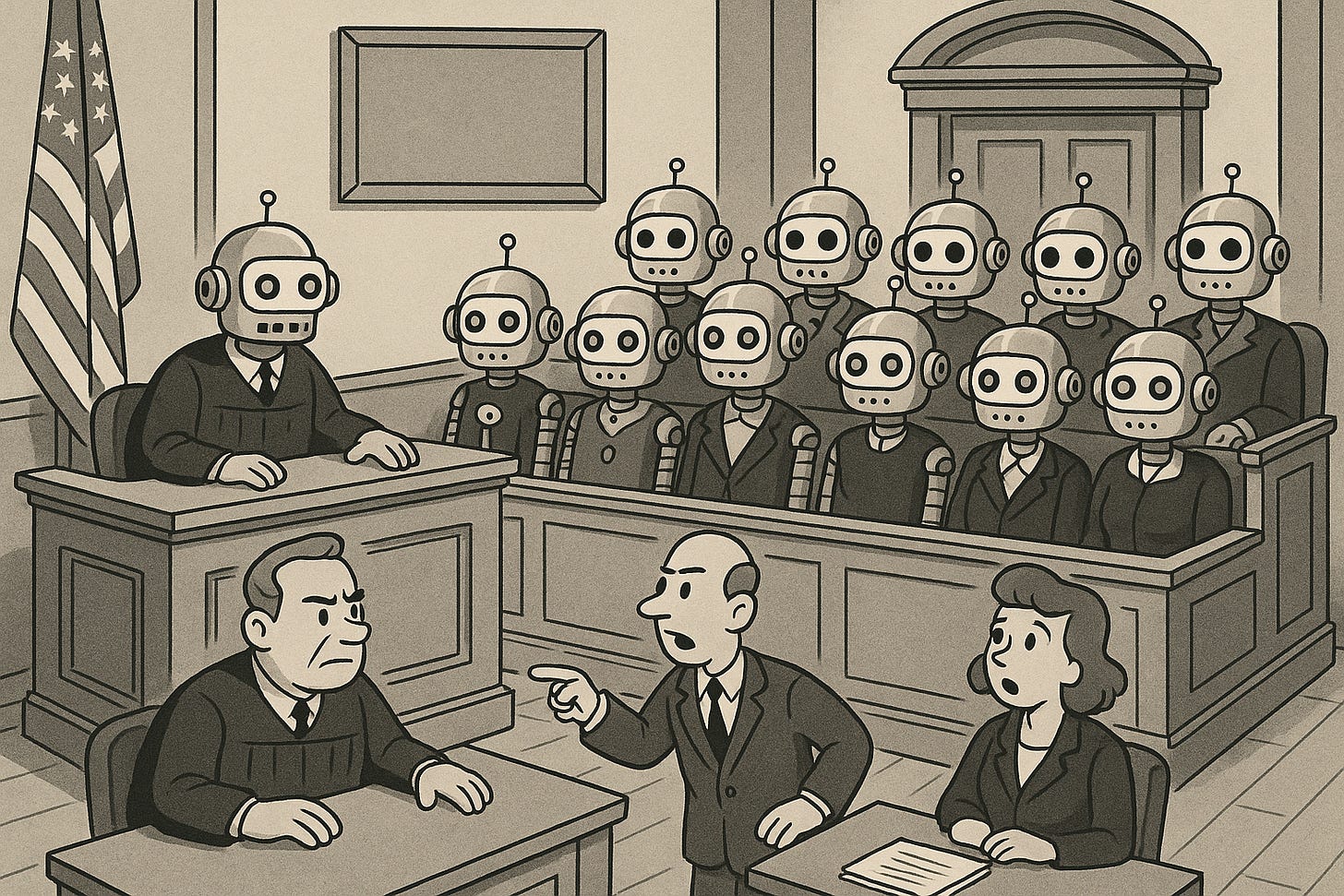

AI on Trial: Can Juries Keep Up?

AI litigation raises urgent questions about due process. Are specialized juries a solution?

The Regulatory Review published an early version of this essay.

The burgeoning field of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has already triggered a wave of legal challenges, and it’s difficult to envision anything but an exponential surge in such lawsuits in the coming years. This rise in AI litigation brings to the forefront a set of complex and unsettling questions: Can ordinary jurors, drawn from diverse backgrounds and levels of expertise, truly render reasoned verdicts when confronted with the intricate technical details of AI, details that might even perplex seasoned AI researchers? And if the answer is no, what alternative mechanisms can our courts employ to safeguard the fundamental right to a jury trial enshrined in the Seventh Amendment?

The conventional understanding of the right to a jury in civil disputes typically involves a two-pronged analysis: first, categorizing the claim as either “legal” or “equitable,” and second, examining the nature of the remedy being sought. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has subtly suggested a third consideration: “the practical abilities and limitations of juries.” This hint, tucked away in a footnote within a relatively obscure 1970 case, has nonetheless prompted some courts to consider the capacity of jurors to grasp the pertinent evidence and legal principles as a factor in determining the availability of a jury trial.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, for example, clearly discerned this subtle suggestion. In the landmark 1980 case In re Japanese Electronic Products Antitrust Litigation, the appellate court overturned the district court’s decision, disagreeing with its conclusion that the sheer complexity of a case “is not a constitutionally permissible reason for striking a party’s jury demands.” According to the Japanese Electronics Products court, fundamental due process “requires some fair assurance that the jury’s findings of fact and applications of legal rules are reasonably correct. When a jury is unable to understand the evidence and the legal rules, it cannot provide this measure of assurance.” Due process, the court elaborated, “guarantees a comprehending factfinder.” Consequently, the court determined that in cases of such “extraordinary complexity” that a jury cannot rationally adjudicate the issues, the Seventh Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial might yield to the due process rights of the parties involved.

While few courts have explicitly adopted the Third Circuit’s articulation of a “complexity” exception to the Seventh Amendment, the application of this principle has not been definitively rejected. Assuming the Supreme Court’s implicit suggestion and the Third Circuit’s reasoning hold legal weight, it appears that cases revolving around generative AI would likely fall under this exception.

Of course, defining what constitutes an issue of “extraordinary complexity” is itself a nuanced challenge. The Third Circuit outlined three key factors for consideration. The first pertains to the overall scope of the lawsuit, encompassing the projected length of the trial, the volume of evidence to be presented, and the number of distinct issues demanding individual scrutiny. The second factor centers on the conceptual difficulties inherent in the legal questions and their underlying factual bases, often indicated by the extent of expert testimony required. Finally, the court considered the challenge of isolating discrete aspects of the case, as reflected in the number of separately contested issues related to individual transactions.

Lawsuits involving generative AI appear poised to satisfy each of these criteria. Regarding the scale of such lawsuits, the initial cases suggest that the widespread adoption of AI and its integration into various economic sectors will lead to suits involving numerous parties and substantial claims for damages—hallmarks of protracted trials.

Similarly, early AI-related lawsuits have already highlighted the inherent complexity of litigating these claims. For instance, OpenAI’s attempt to dismiss a libel suit hinged on the argument that generative AI models occasionally “hallucinate” and produce false information. The underlying reasons for why these models hallucinate, the precise definition of a hallucination, and the feasibility and methods of preventing them all present conceptually demanding inquiries.

Furthermore, concerning the difficulty of segregating distinct aspects of the case, the interconnected nature of AI litigation suggests that understanding one issue may necessitate a grasp of the underlying AI model itself. This interconnectedness further leans towards classifying such suits as extraordinarily complex.

If these due process considerations suggest that traditional juries may not be the optimal factfinders in certain AI cases, the question then becomes: who should fulfill this crucial role?

Fortunately, historical precedent offers a potential solution: “blue ribbon juries,” or juries composed of individuals with specialized knowledge relevant to the case. Throughout history, numerous instances demonstrate the successful use of such expert juries to enhance the likelihood of a competent and rational resolution of disputes.

Consider a few notable examples: In 1394, a jury of “cooks and fishmongers” presided over the prosecution of a defendant accused of selling tainted food. In a 1663 libel trial, the parties empaneled a jury of booksellers and printers, whose expertise would be invaluable in assessing the context and impact of the allegedly libelous material. Early King’s Bench records detail instances of juries composed of clerks and attorneys when the central issues involved the falsification of legal documents by attorneys and extortion by court officials.

This practice also found fertile ground in America. During the 19th century, the states of New York and South Carolina relied on special juries in commercial litigation, recognizing the need for jurors with business acumen in complex financial disputes. Similarly, Louisiana employed merchant juries until 1846, leveraging the expertise of traders in cases involving commercial matters. While shifts in commercial norms and legal frameworks eventually led to the decline of these specialized juries, the underlying principle of matching juror expertise to the complexities of a case remains relevant.

Indeed, while not commonplace in modern civil litigation, the concept of specialized juries has not entirely vanished. A case in point is Delaware, where a 1987 statute empowers state court judges to “order a special jury upon the application of any party in a complex civil case,” explicitly acknowledging the need for expert fact-finding in intricate matters.

While concerns regarding the use of “blue ribbon juries” in cases that might otherwise be heard by traditional juries are understandable and warranted, failing to consider such expert panels in exceptionally complex cases like those involving AI could ultimately undermine the public interest. Impaneling a group of citizens without the necessary technical background in a case that could span months or even years risks a decision rooted in something less than a thorough and rational analysis of the evidence, potentially impacting far beyond the immediate litigants.